“The great stones were in their wild state, so to speak. Some were half covered by the grass, others stood up in cornfields or were entangled and overgrown in the copses, some were buried under the turf. But they were wonderful and disquieting, and as I saw them then, I shall always remember them”

Nash remembering back to his first encounter with the Avebury Megaliths in 1933 (1942); (Nash 1951, 11 – posthumous publication)

Paul Nash (1889 –1946) and I have a history. I vividly remember the first time I saw one of his works, The Menin Road (1918), painted during his tenure as an Official War Artist, during the Great War. It made an immediate, and profound, impact on me. To my young eyes, the burnt out, broken trees, reminded me of the standing stones which I was lucky enough to see peppered throughout the landscapes I roamed as a child. To this day, I cannot explain why I formulated this connection, but it has stuck with me.

When I met this, physically, and psychologically, immense painting again, at the Nash retrospective in 2016 (Tate Britain), I was reduced to tears. The destruction and pain emanating from the canvas literally hit me like a gunshot, but so did the recollection of my childhood interactions with, not just this painting, but also those beautiful megalithic landscapes that, although still physically there, are, for me, forever gone. I still traipse those landscapes, and see those monuments, but now through the eyes of a middle-aged person, who has fought too many battles, rather than that wee, wide-eyed girl.

My dad had a book of Nash’s paintings, so as soon as we got home from London, I dived in. I’d never seen anything like them. Cylinders, that resembled over-extended hay bales, as ‘Equivalents’ for the Megaliths (1935). The giant stones of Avebury painted in an ethereal glory that I couldn’t even begin to comprehend. It was at this point in time that I knew these paintings would stay with me forever. Although at that young age I couldn’t even begin to contemplate just how much both Nash, and his paintings, would steer the course of my life.

“I did not find Surrealism, Surrealism found me”

From a 1942 letter to Herbert Read – Causey 1980, 263

To this day, Nash’s imagination permeates, not only how I perceive and experience landscapes, both ancient and modern, but his art, especially the works produced during the 1930s, influence my own archaeological practice. Through his engagement with Surrealism, whilst channelling the landscape visions of both Blake and Turner, Nash created works that captured both past, present, and future.

I see him everywhere, from the Barbican housing estate in London, to skate parks, and, of course, underpasses. Along with his contemporary, John Piper, Nash questioned the reconstruction of both Avebury and Stonehenge – something that I too have been known to also hold contention with. However, they both formed positive relationships with the archaeologists working at these sites. To some extent, I would suggest, enabling people, such as Stuart Piggott, to begin seeing art and archaeology working together in new, and positive ways.

In this post I’m going to explore these aspects further and discuss how Nash, and the contemporary artists, Jeremy Deller and Mark Leckey, have enabled me to see landscape differently, less empirically. How I wholeheartedly believe that archaeology and art are intrinsically linked. Coming together symbiotically to help create new avenues of engagement, of interpretation, of seeing. So, let’s dive in…

Nash and Avebury

“The landscapes I have in mind are not part of the unseen world in a psychic sense, nor are they part of the unconscious. They belong to the world that lies, visibly, about us. They are unseen merely because they are not perceived…”

Paul Nash, “Unseen Landscapes”, Country Life; 21st May, 1938

Nash first visited Avebury in 1933 and the experience was a profound one. He perceived the surrounding landscape as a ‘living presence’ (1937), and not as “the controlled experience of prehistory offered by Keiller’s restoration” (Smiles 2005, 148). Keiller’s ‘reconstruction’ of Avebury began in the late 1930s, and even drew some rather piqued comments from colleagues. Years later, Stuart Piggott referred to Keiller’s efforts as ‘megalithic landscape gardening’ (Smiles 2005, 148).

Nash, and I, hold similar positions on the somewhat thorny issue of restoration and preservation. Although cordial towards Keiller, Nash disagreed with his approach towards Avebury. As he perceived it, Keiller craved lucidity, whilst the artist yearned for the primordial…

“Avebury may rise again under the tireless hand of Mr Keiller, but it will be an archaeological monument, as dead as a mammoth in the Natural History Museum. When I stumbled over the sarsens in the shaggy autumn grass and saw the unexpected megaliths reared up among the corn stooks, Avebury was still alive” (Nash 1939, 8).

For me, this resonates greatly with what has happened at the Bauhaus Dessau site since it was granted a UNESCO WHS designation. The graphic designer, Erik Spiekermann, has likened the preservation, the sterilisation of this unique building, and, in turn, the people who inhabited it, as the creation of a ‘dead museum’:

“It’s nice and flattering, that it has become a UNESCO world heritage site, but it also means that you can’t change anything. It’s dead, it’s a mausoleum, it’s not even a monument anymore, which is too bad. We shouldn’t celebrate a corpse. We should celebrate the spirit that was in that corpse at one time…”

(Bauhaus 100; originally broadcast on BBC4 on 21st August 2019)

Avebury is part of the UNESCO WHS which also encompasses Stonehenge. Through Keiller’s well-intentioned intervention the site has lost ‘something’. Its enigma? Its sacredness? It’s difficult to define. As archaeologists, especially prehistorians, we can only speculate and hypothesise as to what these huge constructions were erected for. We can reconstruct by examining stratigraphies, cropmarks etc, and placing stones back into positions ascertained from these surveys. However, we can never fully comprehend how the sourcing of the raw materials, their transportation, and erection, truly affected those people 4,500 years ago, especially if (and I truly believe this was the case) they believed the stones, wood, soil and water held the spirits of their ancestors and the deities of their world.

For Nash, this was a key aspect to, not only Avebury, but also a number of other ancient sites within Wessex. Through his art, he proposed; “a mode of engagement with prehistory that works with what cannot be known, what must be intuited” (Smiles 2005, 149).

And this is where Nash, Spiekermann, and myself, link arms. Without this ancient/past working knowledge, lived experience, passion and understanding, Keiller, UNESCO, and others were/are not bringing these places back to life, whether as Later Prehistoric ritual sites, or centres of unique artistic and philosophical creation and exploration. They are presenting static spaces. Spaces that could be deemed sterile. They’re trying to capture a single period in time, and this doesn’t do justice to the architectures, their landscapes, nor the peoples who constructed and engaged with these spaces. I know that this point of view is considered extremely controversial by many, but it is one that I stand by. If you would like to read more about my position, I’ve discussed this in a previous blog post, Ponderings On The Persistence Of Place.

By the late 1930s, Nash was exploring notions of the British landscape through a combination of Surrealism, folklore and archaeology, primarily Later Prehistory. It is this aspect of his work that inspires me deeply and helps to guide my own archaeological practice. As mentioned above, I see Paul Nash everywhere, not just within rural downland contexts, but urban ones too. The most visually obvious (for me) of these inner-city locations is the Barbican housing estate in London. Built between 1965 and 1976, this 40-acre estate, conceived by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, is a masterpiece of Brutalist architectural design.

I have lived in London for nearly 13 years and find this location one of real comfort and peace. I think that one of the main reasons for this connection is the fact that the first time I visited the site I was immediately confronted by Nash’s Equivalents for the Megaliths. They stood before me, so clear, so pristine, sentinels along a processional way that I knew Nash would immediately espy if he was stood alongside me. This strange, foreboding, city began to feel slightly more welcoming to this country girl. I began to actively seek out Nash whenever, wherever, and however I could within the capital, and, later, within other city and townscapes.

1935 saw Nash commissioned, by John Betjeman, on behalf of the Architectural Press, to create Paul Nash’s Dorset: A Shell Guide. He beautifully described Dorset, (the county in which he finally passed over) as “scarred and furrowed by events of the past” (Nash 1936, 9; Fill 2016, 49). This sentence has stuck with me for many years. Nash wrote this within the context of deep history, but, for me, it is only now beginning to resonate within a different concept.

The area where the Barbican estate now stands was levelled to virtually nothing during the bombing raids on London during the Second World War. An area that was ‘scarred and furrowed’ by (recent) past events. Did the architectural design for the Barbican estate unconsciously look back to the deep past for stability? For reconnection with what once was? This is highly unlikely, and is purely theoretical conjecture on my part, but it brings me comfort whenever I walk within the elevated walkways and passageways of this most glorious Brutalist construct. Past, Present, future, together as one.

Simon Grant has described how “Nash had a playful, fantastical way of imagining, and presenting the past” (2016, 14), and it is this aspect of the man, the artist, that I particularly try to channel, and present, within my own archaeological research. Seeing concrete pillars as megaliths, or even their equivalents. Ramps within skater parks as trilithons and winding sacred rivers. Concrete bollards as modern menhirs. Underpasses as liminal places…

For these unconventional ways of seeing, I have Paul Nash to thank. Within a single painting he could convey “the accumulated intenseness of the past as present” (Myfanwy Evans, writing in Axis, 1937; Grant 2016, 14). I would never presume to believe that I can, or could ever, perceive these landscapes in a way even slightly akin to Nash, but his art, his writings, have inspired me to see differently. Yet it isn’t only Paul Nash who drives me to experience landscape and archaeology through different eyes. The contemporary artists Jeremy Deller and Mark Leckey, the latter especially, are enabling me to take my research further; away from more ‘traditional’ archaeological practice, towards a theoretical hybrid encompassing the visual and audial aesthetic, the elemental, the physical, the liminal – landscape punk!

Both Deller and Leckey, possess the wonderful talent of creating a present, whilst having a foot rooted within the past, not as a restraint, but as a means to move forward. Deller’s 2012 creation, Sacrilege, a large inflatable Stonehenge, that ‘popped up’ at various locations within the UK, is an amazing piece of art. Members of the public could physically jump around and within the trilithons and Bluestones of the Stonehenge monument. An act that has been curtailed for many years, although I’m unsure as to whether anyone ever literally jumped around the stones, even during the Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages!

Joking aside, Sacrilege is an important piece of art that enabled public engagement, and connection, with Stonehenge, if albeit through an inflatable bouncy castle. Stonehenge is located within Salisbury Plain, in the far south of England. It isn’t a place that’s easily accessible to most people who live within the UK. However, by touring Sacrilege, the public were able to engage, not just with a brilliant piece of art, that was really good fun too, but also archaeology. Winning on multiple levels!

Deller has also collaborated with archaeologists in later works. A notable example is Wiltshire Before Christ: ‘a collection in honour of Neolithic Britain’ (2019), an exhibition held at The Store X, London, conceived by Deller, photographer, David Sims, and Sofia Prantera of Aries design. The accompanying catalogue contained text by the British prehistorian, Julian Richards.

“I had a sense of being propelled into the future while at the same time reversed into the prehistoric past. A past which held an animistic idea of the world, in which rocks and trees could speak”

(Mark Leckey, in Wallis & Coustou 2019,16).

Mark Leckey has had a significant effect on my research over the past couple of years, especially the Underpasses Are Liminal Places, And Future Ghosts: We Are All Ghosts In The Making projects. The way that he perceives the world resonates deeply with me. His incorporation of prehistory, folklore, hauntology, permeating the landscapes, and soundscapes, of his youth, and which continue to bleed into the present and, possibly the future, have enabled me to formulate my way of approaching these aspects archaeologically. Although we grew up in different parts of England; Leckey is originally from the Wirral, North-West England, and I grew up in the far south and Isle of Wight, upon first exposure to his work; the epic, Dream English Kid, I knew that I had encountered someone who just ‘knew’. The connection that I’ve experienced through Leckey’s work is indeed profound. The Underpasses project, in particular, owes Mark a great debt. Through exploring his images, and sonicscapes, I have been able to convey feelings that have resided within me since early childhood, and turn them, along with archaeological training, into the project that is now unfurling around the world.

For me, as a 21st century archaeologist, art has enabled me to see landscapes, and material culture, differently, less empirically. However, this isn’t a modern phenomenon. As mentioned earlier, both Nash, and his friend, John Piper, formed friendly relations with Keiller and Piggott. Piper and Piggott maintained a life-long friendship after first being introduced to each other during the late 1930s (Smiles 2017, 44). And Piggott recalled watching Nash sketch during the excavation of West Kennet long barrow during the mid-1930s (Bradley 1993, 2), where the two also exchanged small gifts.

Witnessing the artistic interpretations of Nash and Piper first-hand had, I would suggest, a significant effect on Piggott. He acknowledged that art could be a highly effective tool in helping to promote archaeological thought and practice to the wider general public (Smiles 2017, 24). He was particularly impressed with Piper’s representations of the prehistoric landscapes that so enthralled him

“His (Piper’s) extremely sympathetic renderings of the countryside and of the barrows and megaliths and stone circles and hill-forts and what-not would, I think, give a new reality that photographs lack, and would also have the merit of enticing a new public…”

(Letter from Stuart to Peggy Piggott, dated 1st July 1941 – held within the Piggott correspondence archive at the Oxford Institute of Archaeology)

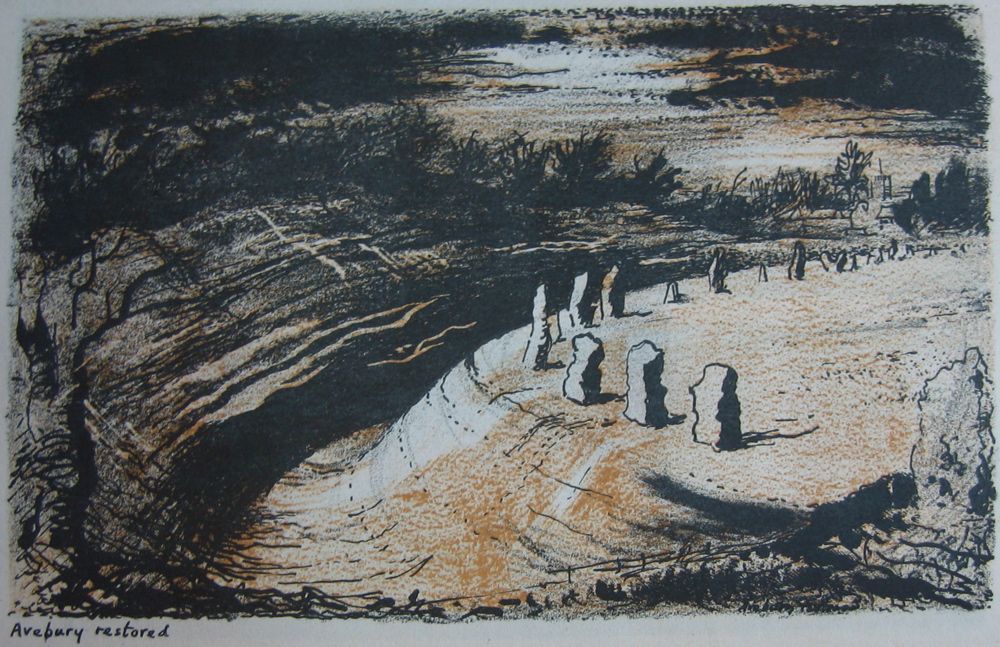

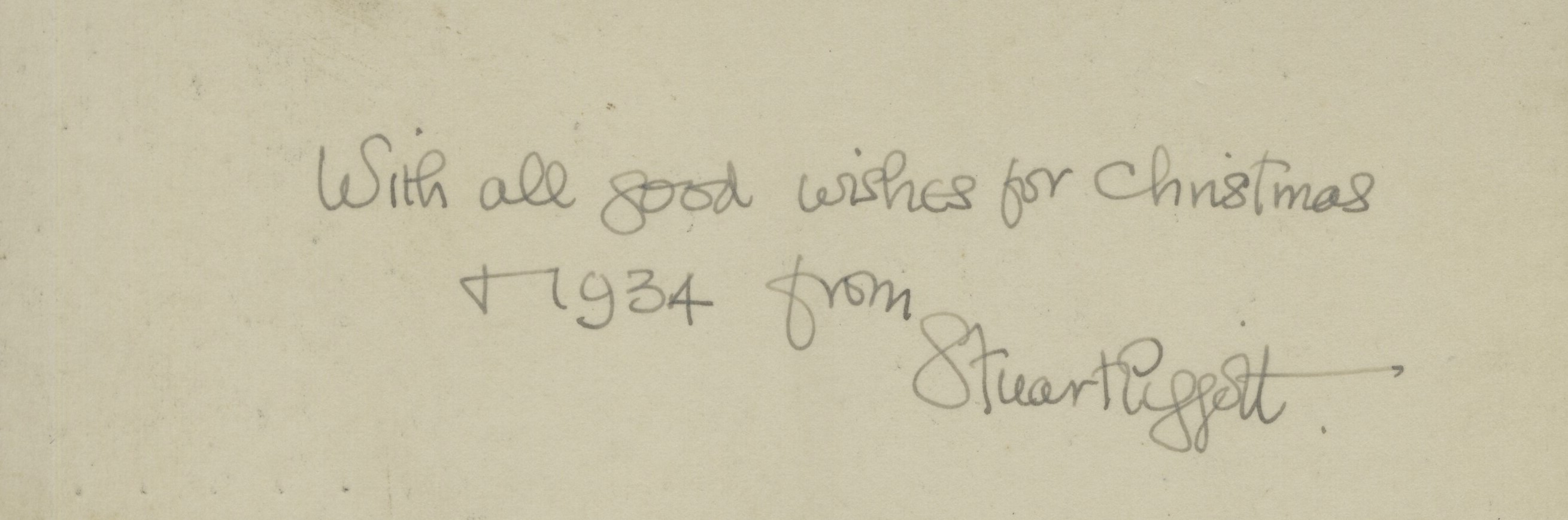

Piggott understood the value of “imaginative representation in capturing the essence of these sites” (Smiles 2017, 24), but I believe he didn’t just consider this within the context of employing artists to depict this spirit. I would argue that Piggott believed it important for archaeologists to be able to artistically convey these sites, and not just through the purely functional, but still beautiful, aspect of finds illustrations and stratigraphic sections, but also through a freer, academically uninhibited, artistic perspective. This belief has been strengthened by a wonderful piece of art that my dear friend, Beth Hodgett, who is based at the O.G.S. Crawford Photographic Archive, Institute of Archaeology, Oxford, sent me a copy of, and which is depicted below.

The first time I saw this image I immediately thought that it was a Nash. I couldn’t believe it when Beth told me that it was by Stuart Piggott and dates to Christmas 1934, the year after Nash’s first visit to Avebury, and the year before Equivalent for the Megaliths was completed.

This wee image has filled me with such joy. I truly believe that art and archaeology do not only complement each other but drive each other onwards. Art has inspired, not only my archaeological research, but that of many colleagues too. Archaeology has inspired art, whether directly or indirectly, for centuries.

So, here we are, at the end of this rather long blogpost, but I did warn you at the beginning, Paul Nash and I have a history… I’m asked by lots of non-archaeologist friends who I would most like to explore the past with. I think a lot of them are rather surprised when I don’t suggest some famous person from history, but, instead, a painter who left this world far too soon. To be able to walk alongside Paul Nash, both within the Wessex downlands and the streets of London, amongst many other places, would be beyond my wildest dreams. As an artist, and a person, he sings to me, and will continue to do so until my end of days. For me, he brought the past, present, and future together poetically. He saw landscapes with the eyes and sensibility of an ancient soul but presented them to the world in a way that only he could. Along with Nicholas Monro, another artistic favourite of mine and Gaffer Lambert’s (dad), Nash showed me that the deep past, the present, and the future, are not separate entities. They are connected, temporally, spiritually, physically.

Thank you for taking the time to ponder with me, and thank you Mr Nash for helping me to see

Thank you to Beth Hodgett and the O.G.S. Crawford Archive for permitting to reproduce the Piggott collage image.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Barbican Life. [Online]

Available at: http://www.barbicanlifeonline.com/history/barbican-estate/

[Accessed 28th December 2020].

Aries, Deller, J., Sims, D. & Richards, J., 2019. Wiltshire Before Christ. London: The Store & Aries.

Bradley, R., 1993. Altering The Earth: The Origins of Monuments in Britain and Continental Europe. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Causey, A., 1980. Paul Nash. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Chambers, E., 2016. Introduction. In: E. Chambers, ed. Paul Nash. London: Tate Publishing, pp. 11 – 22.

Evans, M., 1937. Axis: A Quarterly Review of Contemporary Abstract Painting and Sculpture, Volume 8.

Fill, S., 2016. Paul Nash, Surrealism and Prehistoric Dorset. In: E. Chambers, ed. Paul Nash. London: Tate Publishing, pp. 49 – 58.

Grant, S., 2016. Informal Beauty: The Photographs of Paul Nash. London: Tate Publishing.

Moser, S. & Smiles, S., 2005. Introduction: The Image In Question. In: S. Moser & S. Smiles, eds. Envisioning The Past: Archaeology and the Image. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 1 – 12.

Nash, P., 1936. Dorset: Shell Guide. London: Architectural Press.

Nash, P., 1938. Unseen Landscapes. Country Life, 21st May.

Nash, P., 1939. Landscape of the Megaliths. Art and Education, Issue March.

Nash, P., 1951. Fertile Image. London: Faber.

Smiles, S., 2005. Thomas Guest and Paul Nash in Wiltshire: Two Episodes in the Artistic Approach to British Antiquity. In: S. Moser & S. Smiles, eds. Envisioning The Past: Archaeology and the Image. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 133 – 157.

Smiles, S., 2017. British Art Ancient Landscapes. London: Paul Holberton Publishing for The Salisbury Museum.

Wallis, C. & Coustou, E. eds., 2019. In: Mark Leckey: O’ Magic Power Of Bleakness. London: Tate Publishing.